A Lockdown Overseas: Why year abroad students suffered the most

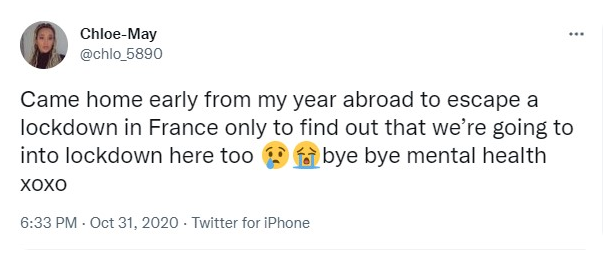

COVID-19 has affected many different sectors of society with language students considered the most unsung of all. For the majority of linguists around the world, the opportunity to take a year abroad whilst at university to plunge into a culture that they have devoted years to is one of the largest attractions to a modern languages degree. However, due to the severity of the coronavirus pandemic engulfing the planet in 2020, many students received the dreaded call to rush home in anticipation of a full-scale lockdown, which saw their hard work, excitement and finances left helplessly in despair. For those fortunate enough to remain at their university abroad or in their placement countries, they too were subject to lockdowns and severe social restrictions. With the implementation of masks and PPE, resulting in a more hostile environment, both their much-awaited societal, cultural and linguistic experiences and progression came to a depressing halt.

It comes as no surprise that fluency is at the top of employers’ demands when interviewing a linguist. Those who graduated in 2022 – by no fault of their own – are at risk of being underqualified and less employable than their forerunners and successors. Not only were students robbed of a year to grow and flourish independently, but also their ability to truly excel and reach a level of fluency in their target language.

There comes a point, in second year of an undergraduate degree, where linguistic development is capped and it becomes evident that the classroom can only go so far. The only effective method to counteract this is to live in a country where the target language is native and spoken widely. The exposure is invaluable, with every interaction gradually closing the gap between the obvious linguistic flaws of student intonation, pronunciation and colloquialisms of a native, serving the ultimate goal of fluency. As a student who is greatly anticipating a year abroad this coming academic year, it is immensely disappointing that the opportunity to meet people from around the world, improve language skills and mature independently was brutally cut short for the students before me.

Universities must be held liable to some extent. Each has a duty of care to provide the best educational opportunities for their students (both from abroad and home), not only in respect of academia but also in respect of student wellbeing and satisfaction. Universities are responsible for providing in-person, campus-based tuition and physical access to facilities, which is promised to all prospective students. Students who pay vast amounts in an attempt to reach their fullest potential have been let down. Their promise of a social experience has been irrevocably stripped away for reasons beyond their control. Universities should picks up the pieces, as opposed to their students, who have lost enough already. More needs to be done and it needs to be done quickly.

Libby Poster (Univeristy of Bristol)